The fight between socialism, communism and Western influence could have ended quite differently for Norway after WW2.

The Labor Party and radicalization

Socialism came through as the result of the immense social inequality Norway had after it’s independence in 1905. Around 90% of the population were either farmers or working class in the industrializing Norway. The Norwegian version of Labor Party was formed in the late 19th century, from many small labor organizations fighting for justice and better living conditions for the working class, and poor people in the countryside. With factory strikes, police revolts and increasing demands from the organizing labor organizations, the Labor Party itself gathered these organizations and politicized their demands. The justice and right to vote changed into a more socialist program by the time representatives were elected into the Parliament in 1903, but the Russian Revolution split the Labor Party into a mess some 15 years later. The Storting (Government) had formed a governing structure based on the British one, and the conservative parties were in majority since the formation in 1884, much backed by the elite in Norway. As they were a small group of wealthy families and industrialists compared to the rest of the population, they kept the circles tight. With increasing prices, an unstable economy and radicalization of the working class after WW1, the Storting feared a communist coup, and did whatever they could to destroy military storages while monitoring the labor organizations closely.

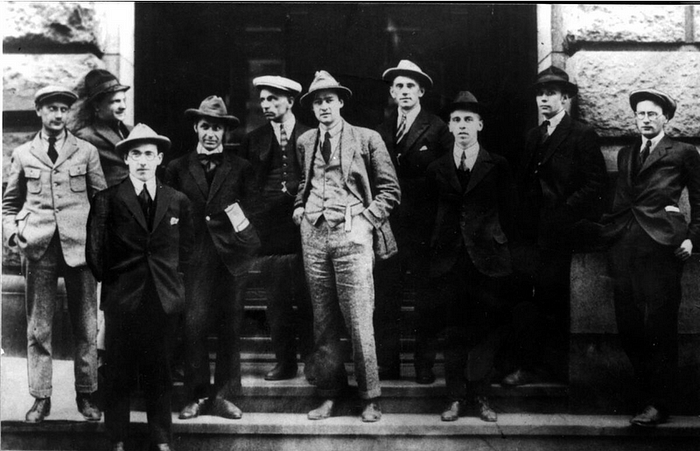

Several individuals appeared in the Labor party who was not only gifted orators, but also aspiring politicians who had traveled in Europe and the US joining different movements there. Martin Tranmæl was one of them, together with Chairman Kyrre Grepp and later Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen. Tranmæl had traveled in the US and joined the IWW, a socialist workers union that opposed the bigger AFL. Einar Gerhardsen had been in Moscow and listened to Lenin. These young men were all schooled in Marxist ideas, socialism and communism, and so when Russian Bolshevik and feminist Alexandra Kollontai came to Norway seeking refugee with her anti-war ideas, she was warmly welcomed into the community. She and Tranmæl became friends for life, and she affected the Labor Party Youth greatly. Kollontai joined Labor Party meetings, contributed to starting Women’s Day the 8th of March and would later become the first female ambassador and attache to Norway and Sweden.

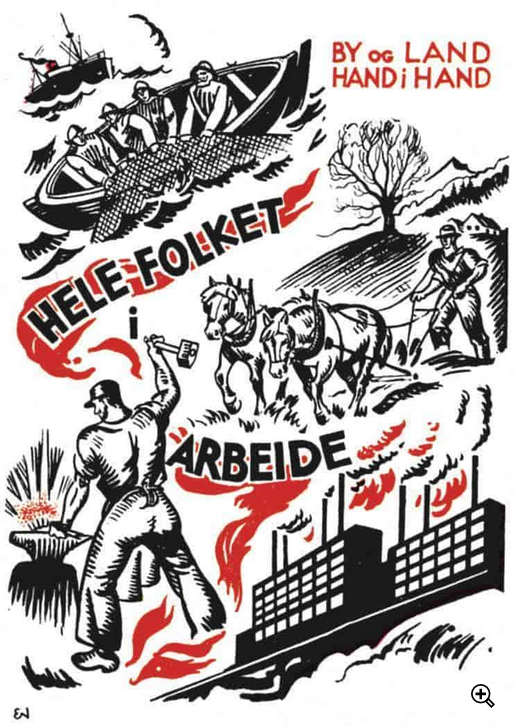

When Kollontai went back to work with Lenin after the Russian Revolution, the Labor Party were already a revolutionary Communist Party, greatly affected by Tranmæl’s encouragement to have a revolution at home as well. Labor Party joined Comintern in 1919 and accepted the Twenty-One Conditions set by Lenin. Tranmæl connected the Party to Moscow, and became the most influential Labor Party politician. Sadly the Conditions split the Labour Party in half after only two years, and the Norwegian Communist party were formed on behalf of more radical Labour-members in 1923. However, the political opponents still viewed the Labour party as Communists, and the party were not invited into the Parliament despite trying to get a wider audience with renewed and less radical ideas, like this poster below for the elections in 1933:

Prime Minister Einar Gerhardsen and Soviet Union

As the Prime Minister Nygaardsvold had led his government in exile from London, the new elections favored Einar Gerhardsen to be the new Labor Party candidate and then Prime Minister. He had led the resistance from home while Tranmæl went to Sweden and the Parliament to London. After being imprisoned in concentration camps by the Nazi Germans, he was saluted to be an honorary example of a great patriot and fellow citizen of the country, despite having no formal political training in the Parliament. Gerhardsen won the elections in 1945 for the Labor Party, and was Prime Minister for a total of 17 years. Due to his immense popularity he got the nickname “Landsfader” which translates to “Pater Patriae” in Roman Latin, or directy as “father of the fatherland”.

Europe after WW2 became divided between the West/East front which continued into the Cold War. Norway had been helped greatly by the Allies during the war, and fear of Soviet Russia in the north had existed for decades already, leading to militarization and hard assimilation policies in the northern regions.

Norway between West and East

Many previous and current party members in the Labor Party had a hard time accepting Norway joining the US and the West. Martin Tranmæl was not that active in the party, but was supporting NATO membership more than previous MP Nygaardsvold. Indeed, Einar Gerhardsen worked hard to implement the Norwegian Communist Party (NKP) back into the Labor Party between 1945–1947, and were critical of Winston Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech from 1946. Despite the Soviet Union were seen as a totalitarian state by most Labor Party members in Norway at the time, Gerhardsen never lost his utopian dreams and memories of the early Soviet Union he himself experienced. He wanted to build a bridge between West and East, while being independent. The Red Army were hailed as heroes for liberating the northern Norwegian regions from Nazi Germany in 1945, and Norway had long traditions with the Barents Sea trade. Gerhardsen extracted the good parts from communism in Russia as shining examples of socialism. The more problematic aspects were excused with Russia’s authoritarian traditions and economic backwardness by both him and the Labor Party.

The Communist coup in Czechoslovakia in 1948 came as a shock, and crushed yet again hope for peaceful cooperation with the Soviet Union. Gerhardsen’s Kråkerøy speech as a reaction to the coup ended his attempts to build a bridge between the communists and Western ideals politically.

“The most important task for Norway’s independence, for democracy and the rule of law is to reduce the Communist Party’s influence as much as possible,” Gerhardsen in the Kråkerøy speech.

Norway joined UN, the Marshall Plan and NATO in 1949, and Gerhardsen continued his years as PM building up armed forces, security policies in the north and sporting social democratic politics together with Sweden and Denmark. He refused to live in the assigned Prime Minister House, but instead lived with his wife in their humble apartment in a Oslo working class district.

Soviet Union agents and the Labor Party

After Stalin’s death, Gerhardsen flew to Russia to again try to soften the relations between the East and West. Soviet diplomats got acquainted with the family in Oslo, and wrote positively how the Gerhardsen family lived in a modest apartment in Oslo East. Rumors swirled around Werna Gerhardsen after her visit to Moscow and Jerevan, as she met with KGB agent Jevgenij Beljakov in a hotel during her visit. Soviet leader Khrusjtsjov opened for more contact with the West after Stalin’s death, and with Norway he was adamant that their relations should improve. Khrusjtsjov visited Norway in 1964, but were not impressed by Gerhardsen’s apartment: “But where do you really live?” he abruptly asked when entering their home.

The 1950’s and 60’s brought a lot of turmoil in the Labor party and for Gerhardsen and his government with their relations to Soviet. What is known today, is only how Gerhardsen tried to balance the careful line between NATO membership, Western intelligence in Norway and the Soviet. He was against placing rockets in Norway which other NATO members reacted to, while stopping the Russians to attack Bodø in 1962: An American U2 plane were shot down over the Soviet Union, and the surviving pilot explained that he was on the way to Bodø town in Norway. At the same time there was also possible infiltration on the inside of the Labor Party. Minister Gunnar Bøe nicknamed “Mono” sold NATO intelligence to the Soviet in the early 60's for money, which again helped him out of his own debts. the police in Norway suspected him for decades but could never find enough evidence to arrest him. Same goes for another minister, Johan Strand Johansen with the KGB nickname “Normann”. Even PM Gerhardsen were listed as “Jan” in the notes from the runaway KGB agent and head of archives, Vasilij Mitrokhin. The archive named after him were published in UK after the agent left Russia in 1992. Between 35–40 Norwegians were listed as “Confidential Contacts” to KGB from 1945, which means that these contacts delivered truthful information to an KGB agent. Such contacts were not told that they were in a scheme, but rather through friendship and trust with the KGB agent, information were leaked. What exactly were done and said is not known even today, but that the ties between the Soviet embassy, the Labor Pary and the Norwegian Communist Party were close, was undoubtedly true.

Ever since the Labor Party got into government the Communist ideas had to be discarded for a more social-democratic line, which built the Norway we have today. But a lot of the party members didn’t let go of their Communist ideals, and the most prominent people inside the party were active for years after the war was over. If not for the Soviet aggression towards other Eastern European countries, and the political opposition pulling Norway towards NATO after the war, things may have been different today.